Even the most dedicated transparency advocates will draw a line when it comes to the disclosure of certain personal information in records. Section 708(b)(6) of Pennsylvania’s Right-to-Know Law (“RTKL”) allows government agencies to withhold personal identification information from public access. In this edition of “Exemptions, Explained,” with legal analysis provided by Appeals Officer Angela Edris, we explore this exemption and how it’s been interpreted by both the Courts and the Office of Open Records (“OOR”).

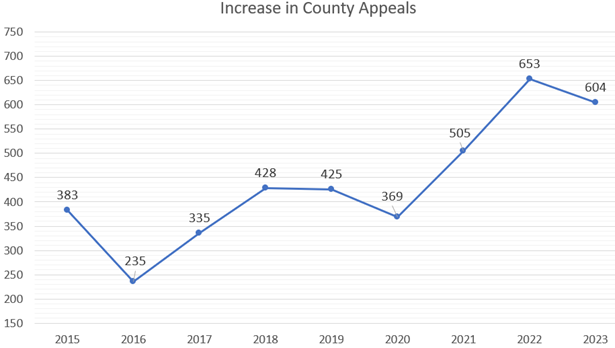

Section 708(b)(6) is, with good reason, one of the most frequently used exemptions by government agencies when redacting or withholding information from public disclosure. As of April 3, 2024, Section 708(b)(6) of the RTKL has been cited in approximately 1,254 OOR appeals.

Section 708(b)(6) of the RTKL protects:

(i) The following personal identification information: (A) A record containing all or part of a person’s Social Security number, driver’s license number, personal financial information, home, cellular or personal telephone numbers, personal e-mail addresses, employee number or other confidential personal identification number. (B) A spouse’s name, marital status or beneficiary or dependent information. (C) The home address of a law enforcement officer or judge. (ii) Nothing in this paragraph shall preclude the release of the name, position, salary, actual compensation or other payments or expenses, employment contract, employment related contract or agreement and length of service of a public official or an agency employee. (iii) An agency may redact the name or other identifying information relating to an individual performing an undercover or covert law enforcement activity from a record.

A multitude of obvious reasons explain the need to protect such sensitive information. The sharing of personal identification information by a government agency leaves individuals vulnerable to identity theft and hacking, and agencies potentially liable to expensive litigation if such breaches occur due to their disclosure of information. The specific withholding of home addresses of law enforcement and judges, as well as identifying information related to undercover law enforcement, upholds a long-standing and widely held belief that the sharing of such information poses a security risk.

Although “personal identification information” is not defined in the RTKL, the Commonwealth Court has found that such information “refers to information that is unique to a particular individual or which may be used to identify or isolate an individual from the general population.”[1] The Court has described it as “information which is specific to the individual, not shared in common with others” and “that which makes an individual distinguishable from another.”[2]

Typically, personal identification information is redacted from agency records when providing them to a requester. Where personal identification information is not an integral part of a record and is able to be redacted, an agency may not withhold the entire record simply because it contains such information.[3]

Email addresses and telephone numbers

Agency-issued email addresses and telephone numbers may be subject to exemption under Section 708(b)(6) if that information is personal to an employee or official.[4] Similarly, personal email addresses and personal telephone numbers, including home and cellular, of employees and/or private citizens may also be withheld and redacted from agency records.[5] However, an email address or telephone number that has been “held out to the public” (ex. on a website) is not considered personal identification information subject to the exemption.[6] Similarly, although fax numbers are not specifically included in the language of the Section, the OOR has found that such numbers, when personal in nature and not held out to the public, are also exempt from access.[7]

Employee numbers and other confidential personal identification numbers

The OOR has found that “employee numbers” and “confidential personal identification numbers” constitute such things like usernames and passwords,[8] examiner identification numbers,[9] operator license numbers and state identification numbers (SID),[10] passport identification numbers,[11] employee payroll numbers,[12] and tenant ID numbers.[13]

However, a Zoom link and corresponding meeting ID and password which was exchanged for purposes of an agency committee meeting is not considered to be a confidential personal identification number under this Section.[14]

Personal financial information

The core of the RTKL is that the public has a right to know how tax dollars are spent; as a result, financial records are generally public. However, an agency’s financial records may include an individual’s financial information that should be withheld. Agencies may withhold “personal financial information, which includes: an individuals’ personal credit, charge or debit card information; bank account information; bank, credit or financial statements; account or PIN numbers and other information relating to an individual’s personal finances.”

In Pa. Dep’t of Conserv. & Nat. Res. v. Office of Open Records,[15] the Court examined the meaning of the phrase “other information relating to an individual’s personal finances,” and found that:

The word “finance” and its variant “finances” have broad meanings. “Finance” has been defined as “money resources, income, etc.” Webster’s New World Dictionary and Thesaurus 240 (2nd ed. 2002). “Finances” has been defined as “the pecuniary affairs or resources of a state, company, or individual.” Webster’s Third New Int’l Dictionary (Unabridged) 851 (1993). Though we could include additional dictionary support, these two alone clearly support a conclusion that an individual’s wages and wage-related information, such as that included in the certified payroll records at issue in these consolidated appeals, represent “money resources, income” and go to “the pecuniary affairs” of an individual. Because this information relates to an individual’s personal finances, the information contained in the certified 6 payroll records falls within the statutory definition of “personal financial information.”

Using the Court’s rationale in DCNR, the Courts and the OOR have found that a variety of information constitutes personal financial information which may be redacted from agency records. Such information includes: individuals’ income and rental amounts in housing records,[16] names of workers in certified payroll records,[17] an agency employee’s salary information from a prior employer,[18] inmate account records that show money in an inmate’s account,[19] bank account information of individuals and private entities,[20] student loan documents that reveal the names, addresses and financial standing of an applicant as well as any other guarantors of the loan,[21] and names of property owners that directly correspond to unredacted tax withholdings.[22]

On the other hand, information which has been found to fall outside the definition of “personal financial information,” and therefore not subject to withholding, includes such things like: severance payments to a former employee,[23] weekly lottery sales data of a retailer operating as a sole proprietor that is collected and maintained by the Department of Revenue,[24] and pension payments paid out by agency.[25] Notably, in addition, the Commonwealth Court has held that an agency’s bank account number is not automatically subject to exemption under Section 708(b)(6).[26]

Home addresses of judges and law enforcement

The home addresses of judges and law enforcement officers are exempt from disclosure, 65 P.S. § 67.708(b)(6)(i)(C). Judges include magisterial district judges[27] and the term “law enforcement officers” includes constables.[28] “The purpose of this unconditional protection afforded to the home addresses of law enforcement officers and judges is to reduce the risk of physical harm/personal security to these individuals that may arise due to the nature of their job.”[29] This exemption also applies where a requester is seeking the address of an individual who also resides at the exempt address.[30] In addition, Section 708(b)(6)(i)(C) is not limited by the retirement status of law enforcement officers and judges.[31]

Spouse’s name, marital status, beneficiary or dependent information

Section 708(b)(6)(i)(C) permits an agency to redact a spouse’s name, marital status, and beneficiary or dependent information. Such information includes the name of a dependent on a health insurance policy[32] or tax withholding information that reveals marital status or dependent information.[33] The OOR has also found that a record of a life partnership formation and/or termination is a record that reflects the “marital status” of an individual.[34] This Section does not protect the dollar amount of premiums paid by an agency for an individual employee for medical benefits coverage.[35]

Names and Compensation of Public Employees and Officials, among other things, are public.

Significantly, Section 708(b)(6) clearly indicates that certain information is public and is not intended to be covered by the Section. Section 708(b)(6)(ii) essentially sets forth the general rule that an agency employee or public official’s name, position, salary, actual compensation, or other payments or expenses are public information.

Under Section 708(b)(6)(ii), the amounts of employer-paid benefits, such as amounts paid for health insurance,[36] agency payments to pensions and retirement benefits paid for public employees[37] are subject to public access. However, descriptions of voluntary employee contributions and employee-elected benefits are exempt from disclosure under Section 708(b)(6)(i)(A).[38]

The only employee or official name that Section 708(b)(6) expressly permits an agency to withhold is the name of an individual, whether a police officer or not, who is engaged in undercover or covert work.[39] Except for those engaged in such work, the personal identification exemption does not permit the redaction of the identities of law enforcement. While certain other RTKL exceptions might be utilized to shield identities or information regarding law enforcement, given the inherent personal security concerns,[40] the general rule is that names of employees and public officials, along with salary and compensation are public.

Likewise, employment contracts, employment-related contracts or agreements and length of service of a public official or an agency employee are also considered to be public information as well. An insurance policy for public employees is considered “an employment-related contract” for health or dental coverage for employees, and payments for those policies by a public agency are “financial records” of the agency.[41] There is a strong public interest in knowing the remuneration received by agency employees and officials, both past and present.[42]

Information that is not protected under Section 708(b)(6)

In addition, while the list of protected information in Section 708(b)(6) is wide-ranging, the Section does not protect all information that one might consider to be personal in nature from disclosure. Two types of such information which are often seen by the OOR in appeal proceedings are birth dates and home addresses. While not expressly covered by Section 708(b)(6), such information has been found to be protected from disclosure, at least in part by Pennsylvania’s constitutional right to privacy. While the right to privacy will be covered in more detail in another blog post in the future, it is important for the purposes of our discussion here to just note that where certain information that is personal in nature is not explicitly protected under Section 708(b)(6), it is possible that such information may be protected under the right to privacy, particularly where a privacy interest is implicated. Likewise, information that is personal in nature should also be analyzed in the context of the RTKL’s other exemptions to determine whether those exemptions apply.[43]

Other information that has been held to lack protection under Section 708(b)(6) of the RTKL include a person’s signature,[44] an individual’s photograph, names of annuitants,[45] license plate numbers and vehicle identification numbers.[46]

[1] Del. County v. Schaefer, 45 A.3d 1149, 1153 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2012).

[2] Id.

[3] See 65 P.S. § 67.706.

[4] Office of the Lieutenant Gov. v. Mohn, 67 A.3d 123 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2013) abrogated in part on other grounds, Pa. State Educ. Ass’n v. Commonwealth, 148 A.3d 142 (Pa. 2016); Pa. State Educ. Ass’n, 148 A.3d 142; Krug v. Bloomsburg Univ. of Pa., OOR Dkt. No. AP 2018-1589, 2018 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 1419.

[5] Gentner v. Palisades School District, OOR Dkt. AP 2021-2537, 2022 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 558;

[6] Pa. State System of Higher Education v. The Fairness Center, No. 1203 C.D. 2015, 2016 Pa. Commw. Unpub. LEXIS 245 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2016); Zeyzus v. Pa. Game Commission, OOR Dkt. AP 2022-2336; 2022 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 2887.

[7] Abrams v. Morrisville Borough School, AP 2023-0165, 2023 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 779.

[8] Kneller v. PCCD, OOR Dkt. AP 2022-1206, 2022 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 1789.

[9] Baker v. Pa. Dep’t of Transportation, OOR Dkt. AP 2022-2838 2023 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 476.

[10] Barry v. Pa. Office of Admin., OOR Dkt. AP 2020-1210 2020 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 2596.

[11] Ullery v. Dep’t of Health, OOR Dkt. AP 2017-1420 2018 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 77.

[12] Feliciano v. Phila. District Attorney’s Office, OOR Dkt. No. AP 2019-0275, 2019 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 286.

[13] O’Brien v. Phila. Housing Auth., Dkt. No. AP 2018-1722, 2018 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 1447.

[14] Haring v. Pennridge School District, OOR Dkt. AP 2021-0979, 2021 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 1302.

[15] Pa. Dep’t of Conversation and Natural Resources (DCNR) v. Office of Open Records, 1 A.3d 929 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2010)

[16] O’Brien, supra.

[17] DCNR, supra.

[18] McClain v. Governor’s Office of Admin., OOR Dkt. AP 2019-0857, 2019 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 658.

[19] Boyd v. Pa. Dep’t of Corr.,No. 206 C.D. 2012, 2013 Pa. Commw. Unpub. LEXIS 275 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2013).

[20] Towne v. Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Auth., OOR Dkt. AP 2021-0292, 2021 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 307.

[21] Darr v. PHEAA, OOR Dkt. AP 2019-0088, 2019 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 260.

[22] Nicholl and Charles Jones LLC v. Montoursville Area School Dist., OOR Dkt. AP 2023-2914, 2024 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 373; but compare Butler Area Sch. Dist. v. Pennsylvanians for Union Reform, 172 A.3d 1173 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2017 (finding that a property tax assessment list should be provided to the requester because it was statutorily public and documented only the ownership of real property, rather than identifying facts about an individual, such as their home address).

[23] Coladonato v. Antrim Township, OOR Dkt. AP 2022-2662, 2023 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 193.

[24] Haverstick v. Dep’t of Revenue, OOR Dkt. AP 2023-2908, 2024 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 412.

[25] Ciavaglia v Bucks County, OOR Dkt. AP 2019-1064, 2019 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 894.

[26] Borough of W. Easton v. Mezzacappa, 116 A.3d 1190, 2015 Pa. Commw. Unpub. LEXIS 402 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2015).

[27] Rose v. Westmoreland County, OOR Dkt. AP 2024-0391, 2024 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 586.

[28] Grove v. Constable John-Walter Weiser, OOR Dkt. AP 2018-0457, 2018 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 523.

[29] State Emples. Ret. Sys. v. Fultz, 107 A.3d 860 (Pa. Commw. 2015).

[30] Fultz, supra.

[31] See Handerhan v. Mt. Carmel Borough, OOR Dkt AP 2010-0728, 2010 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 725.

[32] Tanner v. Elkland Borough, OOR Dkt. AP 2015-0433, 2015 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 430.

[33] Mezzacappa v. Colonial Intermediate Unit 20, OOR Dkt. AP 2019-0880, 2019 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 768.

[34] Paige v. Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations, OOR Dkt. AP 2019-1983, 2019 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 2198.

[35] Sorenson v. Northwestern Lehigh School District, OOR Dkt. AP 2013-2028, 2013 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 1226.

[36] Bridy v. City of Shamokin, OOR Dkt. AP 2013-0430; 2013 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 300.

[37] Edgell v. Pennridge Sch. Dist., OOR Dkt. AP 2013-1242, 2013 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 721.

[38] Mezzacappa, supra.

[39] Pa. State Police v. McGill, 83 A.3d 476 (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2013).

[40] See Stein v. Office of Open Records, No. 1236 C.D. 2009, 2010 Pa. Commw. Unpub. LEXIS 313 (Pa. Commw. Ct. May 19, 2010) (first names of corrections officers are not public records as such information falls within the personal security exemption set forth in Section 708(b)(l)(ii) of the RTKL).

[41] Sorenson, supra.

[42] Coladonato, supra.

[43] For example, see Governor’s Office of Admin. v. Purcell, 35 A.3d 811, (Pa. Commw. Ct. 2010) (finding, based on the evidence presented, that disclosure of the full dates of birth of state employees would result in substantial and demonstrable risk to the employees’ personal security due to the risk of identity theft).

[44] Murray v. Pa. Dep’t of Health, OOR Dkt. AP 2017-0461 2017 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 1361.

[45] Bauder and the Pittsburgh Tribune Review v. City of Pittsburgh, OOR Dkt. AP 2017-0499, 2017 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 1002.

[46] George v. Penn Twp., OOR Dkt. AP 2023-2719, 2023 PA O.O.R.D. LEXIS 2886.